People mistake themselves for islands - that their existence starts and ends at the boundaries of their physical forms. But the reality is, we cannot be described so simply as singular solid entities. We’re more accurately described as an atmosphere, because there does not exist a single point or surface where our body atoms stop and the air atoms begin.

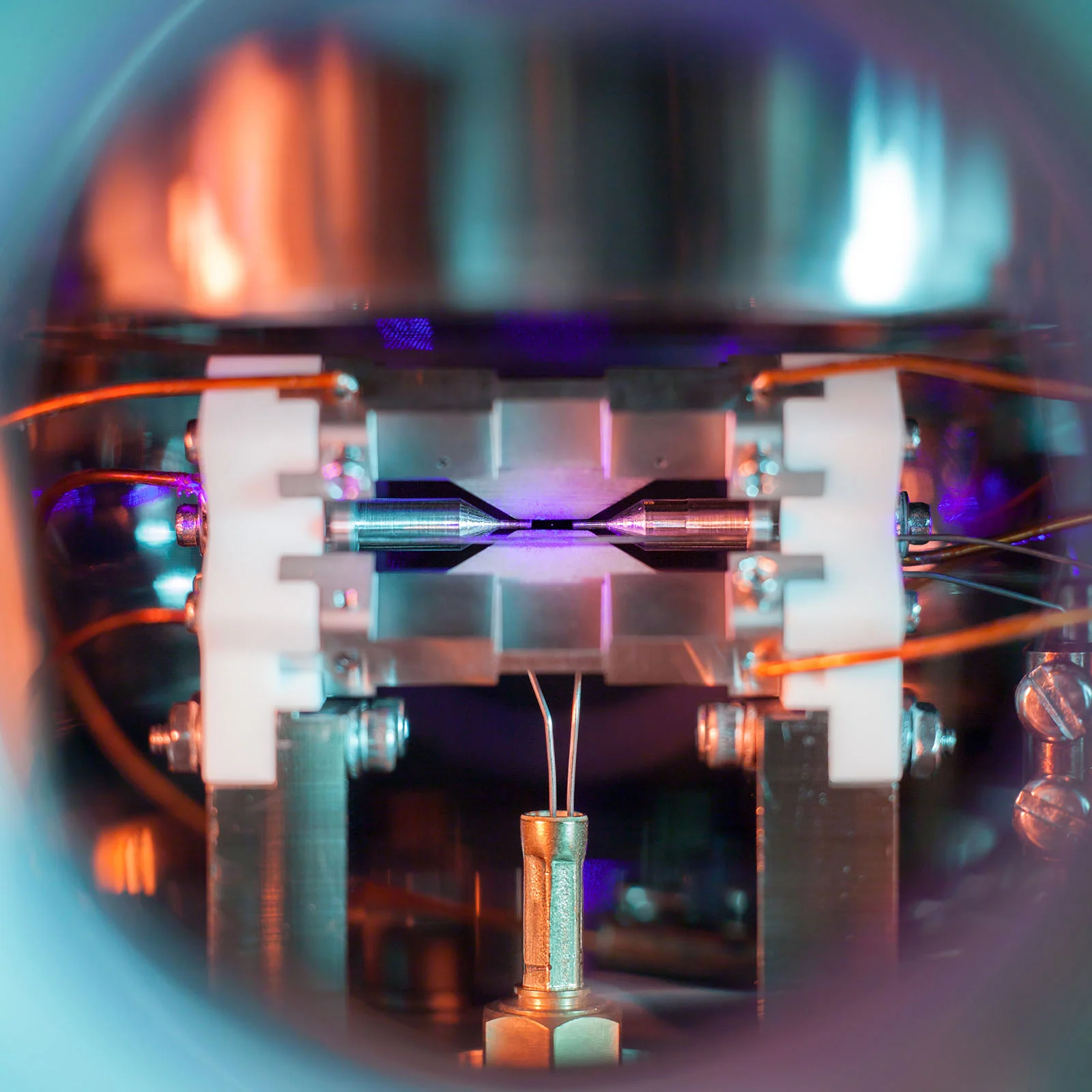

The loneliest photograph I have seen is that of a strontium atom. In 2018, the first-place award of the UK’s Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council photography contest was awarded to David Nadlinger from the University of Oxford. With immense effort, requiring an ultra-vacuum system, vaporized metal, and electromagnetic forces, David Nadlinger was able to capture the photo of a singular atom. The isolated strontium atom shone as a tiny spec of light in a dark void and ever since, any feeling that I have called loneliness has not compared.

We do not sit alone in a vacuum as that strontium atom did. If we get quiet enough, sit still enough, we may start to feel our edges soften. The atoms at the visual edge of our skin drifting out and intermingling with the atoms in the surrounding air. We may, then, find expansion through atomic vibrations sent from our throat to another’s ears, in the exchange of particles in the mouth of a lover, and in the burst of oxytocin molecules as our atoms press and mix into another. Our consciousness is formed by happenstance, when just the right unique combination of the same atomic building blocks that form the ground beneath and the stars above fall and pull each other into place. We are the universe; we fold into ourselves like dough, and we rise inside it, boundless.

Though that strontium atom could only be kept in isolation for a moment before being pulled to return to its kinship, its moment of solitude has taught me that solitude is not a state, but rather, a shape we impose upon our world where division is easier to see than unity.